Invisible Highways

Like most people living near the I-35W bridge, I hustled to the scene of destruction within a few minutes of the collapse. It was still another ten minutes before the cops showed up, so the crowd was able to approach very close to the edge of the north bank of the river. What we saw took our breath away: it looked like someone had dropped a concrete ribbon directly across the river, from bank to bank, and littered it with small toy cars. For me, there was an overwhelming sense of displacement--my brain couldn't seem to process the juxtaposition of chunks of highway and cars in a riverbed. (The Dadaists, and to some extent the Surrealists, were fans of juxtaposition, because they believed it would cut a short-circuit through your brain and tap into a deeper elemental response. Maybe they were right.)

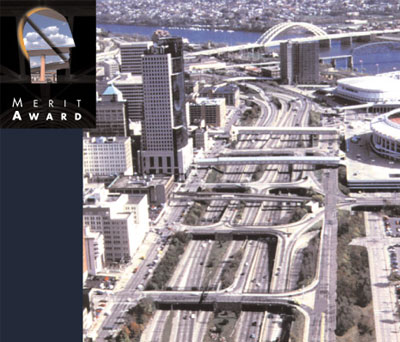

Part of this feeling of displacement, however, emanates from the fact that the bridge in question was designed to be hidden, in a fashion, from pedestrians. Most highways that pass through cities (such as the trenched highway in Cincinnati, pictured above) are designed so that they do not impinge upon pedestrian life. This means shielding them visually by erecting concrete divider walls, "sinking" the highways below grade ("trenching" them), or elevating them well above normal traffic (see Taipei for more). Although I, like most Twin Citians, drove on that bridge several times every week, I was very much unaware of its presence when walking in my neighborhood (even though the bridge passes directly through it).

This unawareness, from a pedestrian perspective, is a testament to good urban planning. Highways are noisy, ugly beasts that, if exposed, can ruin the experience of a city. Planners do a great job of concealing the fact that a 100-foot wide ribbon of concrete, upon which thousands of 3000-pound hunks of metal hurtle at 70 mph all day long, pass through neighborhoods of great population density.

With the I-35W bridge now lying in the Mississippi river, I wonder if its replacement will again embody the principle of concealment of urban highways. Though it will still be visible directly from the riverbank, will engineers again try to hide its existence from the residents of Dinkytown, Marcy-Holmes, and the West Bank of UMinn?

2 Comments:

What city is that? It's terrible!

Well either way you're going to see a much different replacement bridge then the one that collapsed. It won't be that same steel box frame design. Look for a somewhat larger and mostly concrete bridge. Its still going to have to have two piers on each bank simply because you can't really build piers mid river because of swift moving ice flows in the winter. I may be wrong and some new technology may be used, but with the high level of attention to it from now on I don't see it. I don't think you will see any radical or new technology composite designs but I think you will see a very sturdy, very concrete and rebar type of bridge and almost none of the steel truss design of the old one. You're going to see two very large piers and they can get away with that because they will remain in the natural valley below, unseen on street level Minneapolis as was the old bridge.

Also of note, if you look at pictures of the bridge before the collapse you notice it juts out over its base by at least 2 lanes on each side. I'm wondering if additional lanes were added as traffic increased over the years? Did this add to the stress on this bridge? Or maybe that was the way it looked when built in 1967.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home